The Violet Hour Anthology

NICK CAVE - ON GRIEF

Cynthia, a fan from Vermont asks:

“I have experienced the death of my father, my sister, and my first love in the past few years and feel that I have some communication with them, mostly through dreams. They are helping me. Are you and Susie feeling that your son Arthur is with you and communicating in some way?”

Nick Cave responds:

Dear Cynthia,

This is a very beautiful question and I am grateful that you have asked it. It seems to me, that if we love, we grieve. That’s the deal. That’s the pact. Grief and love are forever intertwined. Grief is the terrible reminder of the depths of our love and, like love, grief is non-negotiable. There is a vastness to grief that overwhelms our minuscule selves. We are tiny, trembling clusters of atoms subsumed within grief’s awesome presence. It occupies the core of our being and extends through our fingers to the limits of the universe. Within that whirling gyre all manner of madnesses exist; ghosts and spirits and dream visitations, and everything else that we, in our anguish, will into existence. These are precious gifts that are as valid and as real as we need them to be. They are the spirit guides that lead us out of the darkness.

I feel the presence of my son, all around, but he may not be there. I hear him talk to me, parent me, guide me, though he may not be there. He visits Susie in her sleep regularly, speaks to her, comforts her, but he may not be there. Dread grief trails bright phantoms in its wake. These spirits are ideas, essentially. They are our stunned imaginations reawakening after the calamity. Like ideas, these spirits speak of possibility. Follow your ideas, because on the other side of the idea is change and growth and redemption. Create your spirits. Call to them. Will them alive. Speak to them. It is their impossible and ghostly hands that draw us back to the world from which we were jettisoned; better now and unimaginably changed.

With love, Nick.

Rainer Maria Rilke - To Claire Goll (The Dark Interval: Letters for the Grieving Heart)

Liliane,

Before writing this to you I had torn up another letter that I had written two nights ago, since I do not feel like telling you anything “general” at the moment when you demand my empathy and attention. And yet, tell me, how to find those particular words that will be valid exactly for you, since I have learned only via the abbreviated announcement of the type of affliction that now puts you in an immensely difficult test.

You see, I think that now, since you are confronted for the first time with having to suffer death in the death of the person who is so infinitely close to you, all of death (somehow more than only your own, possible death), that now is the moment when you are most capable of truly perceiving and recognising the pure secret which, believe me, is not that of death but of life.

Now it is necessary, in an unspeakably and inexhaustibly magnanimous gesture of pain, to include death in life, all of death, since through someone previous to you it has moved within your reach (and you have become related to it). Make it part of life as something no longer to be rejected, no longer denied. Pull it toward you with all your strength, this horrific thing, and as long as you cannot do that, pretend that you are comfortable and familiar with it. Don’t scare it off by being scared of it (like everyone else). Interact with it or, if that is still too much of an effort for you, at least hold still so that it can get very close, that always chased-off creature of death, and let it cuddle up to you. For this, you see, is what death has become for us: something always chased away that no longer had a chance of revealing itself to us. If at the moment when it hurts and devastates us, death were treated by even the simplest person with some familiarity (and not with horror), what confessions would it share when it - finally - passed over to him! Only a small moment of open-mindedness toward it, a brief suppression of prejudice, and it is ready to share infinite intimacies that would overwhelm our tendency to endure it with trembling hesitation. Patience Lilliane, nothing but: patience.

Once you have been granted access to the Whole and thus been initiated, you solemnly celebrate your own true independence. You become more protective and more capable of granting protections exactly to the extent that you have lost and now lack protection. The solitude into which you were cast so violently makes you capable of balancing out the loneliness of others to exactly the same degree. And as your own sense of difficulty is concerned, you will soon realise that is has posited a new measure for your existence and a new standard for your suffering and endurance.

I offer a bit of advice, Liliane; I am trying nothing more but to be close to you with these simple words. On some later occasion you will tell me whether they were of any use, for nobody comes close to true assistance and consolation, except by an act of grace.

Rilke

Carl Sagan - Pale Blue Dot

Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there--on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

Michel Faber - Restraining Order (from Undying: A Love Story)

Unshaven, shabby and unwashed,

I haunt the place where we last slept

together, and refuse to leave.

Why no one calls the cops to move

me on, I do not understand.

Surely someone will lay a hand

on my clammy shoulder, and say

’Nothing more to see.’

In the beginning, all that love

was awfully romantic in its way,

but now the novelty's worn thin

and normalcy is overdue.

This loyalty to what’s dead and gone,

this clinging to what’s no longer

mine; its borderline obsessed.

Give it a rest.

A polite suggestion, buddy:

Give her some space. Steer clear

of where you think she ought to be,

She won’t be there. Instead, why not

give some thought to personal hygiene.

Adopt a healthier diet. Keep well-hydrated.

Find other topics of conversation.

Maybe join a group of folk like you,

to talk things through.

By all means take some time

to grieve, but don't let it become

excessive. Accept the situation:

you’ve lost her. Try not to be

possessive.

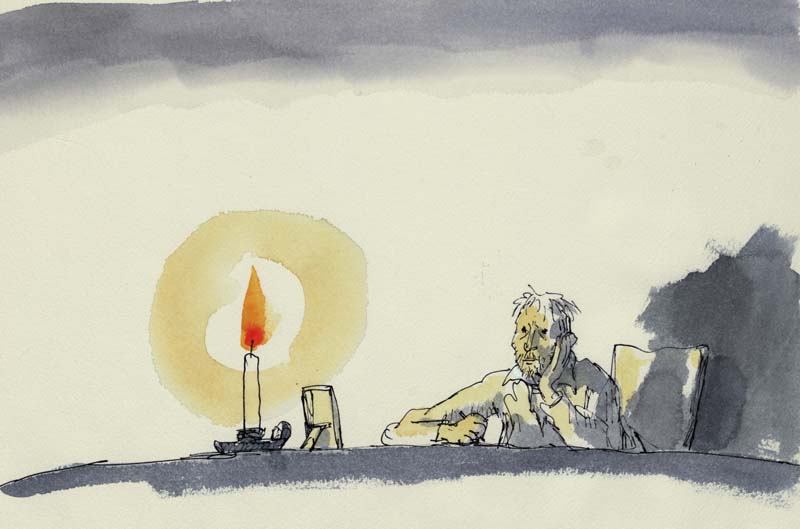

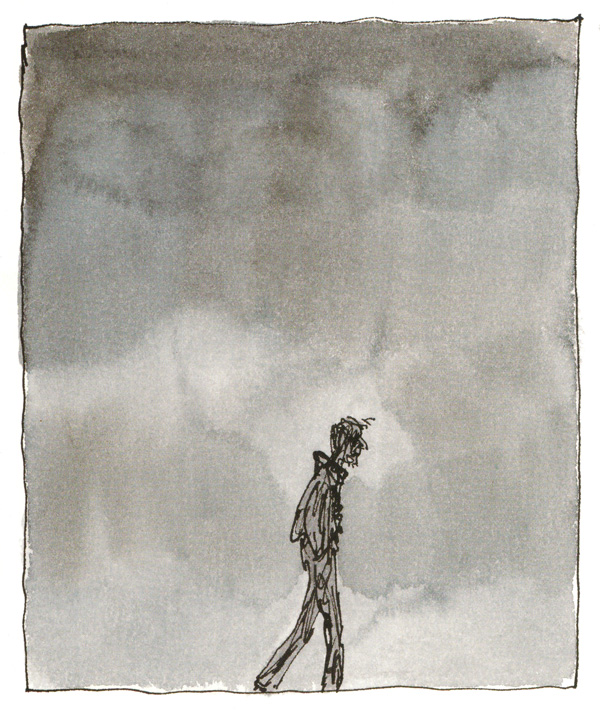

Max Porter - Grief is the Thing With Feathers (excerpt)

DAD

Four or five days after she died, I sat alone in the living room wondering what to do. Shuffling around, waiting for shock to give way, waiting for any kind of structured feeling to emerge from the organizational fakery of my days. I felt hung-empty. The children were asleep. I drank. I smoked roll-ups out of the window. I felt that perhaps the main result of her being gone would be that I would permanently become this organizer, this list-making trader in clichés of gratitude, machine-like architect of routines for small children with no Mum. Grief felt fourth- dimensional, abstract, faintly familiar. I was cold.

The friends and family who had been hanging around being kind had gone home to their own lives. When the children went to bed the flat had no meaning, nothing moved.

The doorbell rang and I braced myself for more kindness. Another lasagne, some books, a cuddle, some little potted ready-meals for the boys. Of course, I was becoming expert in the behavior of orbiting grievers. Being at the epicenter grants a curiously anthropological awareness of everybody else; the overwhelmeds, the affectedly lackadaisicals, the nothing so fars, the overstayers, the new best friends of hers, of mine, of the boys. The people I still have no fucking idea who they were. I felt like Earth in that extraordinary picture of the planet surrounded by a thick belt of space junk. I felt it would be years before the knotted-string dream of other people’s performances of woe for my dead wife would thin enough for me to see any black space again, and of course–needless to say–thoughts of this kind made me feel guilty. But, I thought, in support of myself, everything has changed, and she is gone and I can think what I like. She would approve, because we were always over-analytical, cynical, probably disloyal, puzzled. Dinner party post-mortem bitches with kind intentions. Hypocrites. Friends.

The bell rang again.

I climbed down the carpeted stairs into the chilly hallway and opened the front door.

There were no streetlights, bins or paving stones. No shape or light, no form at all, just a stench.

There was a crack and a whoosh and I was smacked back, winded, onto the doorstep. The hallway was pitch black and freezing cold and I thought, ‘What kind of world is it that I would be robbed in my home tonight?’ And then I thought, ‘Frankly, what does it matter?’ I thought, ‘Please don’t wake the boys, they need their sleep. I will give you every penny I own just as long as you don’t wake the boys.’

I opened my eyes and it was still dark and everything was crackling, rustling.

Feathers.

There was a rich smell of decay, a sweet furry stink of just-beyond-edible food, and moss, and leather, and yeast.

Feathers between my fingers, in my eyes, in my mouth, beneath me a feathery hammock lifting me up a foot above the tiled floor.

One shiny jet-black eye as big as my face, blinking slowly, in a leathery wrinkled socket, bulging out from a football-sized testicle.

SHHHHHHHHHHHHH.

shhhhhhhh.

And this is what he said:

I won’t leave until you don’t need me any more.

Put me down, I said.

Not until you say hello.

Put. Me. Down, I croaked, and my piss warmed the cradle of his wing.

You’re frightened. Just say hello.

Hello.

Michael Rosen - Sad Book

This is me being sad.

Maybe you think I’m happy in this picture.

Really I’m sad but pretending I’m happy.

I’m doing this because I think people won’t like me if I look sad.

Sometimes sad is very big.

It’s everywhere. All over me.

Then I look like this.

And there’s nothing I can do about it.

What makes me most sad is when I think about my son Eddie. He died. I loved him very, very much but he died anyway.

Sometimes this makes me really angry.

I say to myself, “How dare he go and die like that?

How dare he make me sad?”

Eddie doesn’t say anything,

because he’s not here anymore.

Sometimes I want to talk about all this to someone.

Like my mum. But she’s not here anymore, either. So I can’t.

I find someone else. And I tell them all about it.

Sometimes I don’t want to talk about it.

Not to anyone. No one. No one at all.

I just want to think about it on my own.

Because it’s mine. And no one else’s.

Sometimes because I’m sad I do crazy things — like shouting in the shower…banging a spoon on the table or making my cheeks go whoof whoof whoof

Sometimes because I’m sad I do bad things. I can’t tell you what they are, they’re too bad and it’s not fair to the cat.

Sometimes I’m sad and I don’t know why.

It’s just a cloud that comes along and covers me up.

It’s not because Eddie’s gone.

It’s not because my mum’s gone. It’s just because.

Maybe its because things now aren’t like they were a few years ago

Like my family. Its not the same as it was a few years ago.

So what happens is that there’s a sad place inside me because things aren’t the same.

Ive been trying to figure out ways of being sad that don’t hurt so much. Here’s some of them.

I tell myself that everyone has sad stuff. I’m not the only one. Maybe you have some too?

Every day I try to do one thing I can be proud of. Then when I go to bed I think very very very hard about this one thing. I tell myself that being sad isn’t the same as being horrible. I’m sad not bad.

Every day I try to do one thing that means I have a good time. It can be anything.

So long as it doesn’t make anyone else unhappy.

And sometimes I write about sad. Where is sad? Sad is anywhere. It comes along and finds you.

When is sad? Sad is any time. It comes along and finds you.

Who is sad? Sad is anyone that comes along and finds you.

I write sad is a place that is deep and dark like the space under the bed.

Sad is a place that is high and light like the sky above my head

When its deep and dark I dare not go there

When it’s high and light I want to be thin air

This last bit means I don’t want to be here, I just want to disappear.

But sometimes I find myself looking at things. Faces at a window. A crane and a train full of people going past.

And then I remember things. My mum in the rain. Eddie walking along the street laughing and laughing and laughing

Doing his old-man act in the school play.

The two of us playing catch on and off the sofa.

And birthdays…I love birthdays

Not just mine. Other peoples as well.

Happy birthday to you and all that.

And candles. There must be candles.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie - Notes on Grief (written for The New Yorker’s ‘Personal History')

From England, my brother set up the Zoom calls every Sunday, our boisterous lockdown ritual, two siblings joining from Lagos, three from the United States, and my parents, sometimes echoing and crackly, from Abba, our ancestral home town, in southeastern Nigeria.

On June 7th, there was my father, only his forehead on the screen, as usual, because he never quite knew how to hold his phone during video calls.

“Move your phone a bit, Daddy,” one of us would say. My father was teasing my brother Okey about a new nickname, then he was saying that he hadn’t had dinner because they’d had a late lunch, then he was talking about the billionaire from the next town who wanted to claim our village’s ancestral land. He felt a bit unwell, had been sleeping poorly, but we were not to worry.

On June 8, Okey went to Abba to see him and said that he looked tired. On June 9, I kept our chat brief so that he could rest. He laughed quietly when I did my usual playful imitation of a relative. “Ka chi fo,” he said (“Good night”). His last words to me. On June 10, he was gone. My brother Chuks called to tell me, and I came undone.

My four-year-old daughter says I scared her. She gets down on her knees to demonstrate, her small clenched fist rising and falling, and her mimicry makes me see myself as I was, utterly unravelling, screaming and pounding the floor. The news is like a vicious uprooting. I have yanked away from the world I have known since childhood. And I am resistant: my father read the newspaper that afternoon; he joked with Okey about shaving before his appointment with the kidney specialist in Onitsha the next day; he discussed his hospital test results on the phone with my sister Ijeoma, who is a doctor, and so how can this be? But there he is. Okey is holding a phone over my father’s face, and my father looks asleep, his face relaxed, beautiful in repose. Our Zoom call is beyond surreal, all of us weeping and weeping and weeping, in different parts of the world, looking in disbelief at the father we adore now lying still on a hospital bed. It happened a few minutes before midnight, Nigerian time, with Okey by his side and Chuks on speakerphone. I stare and stare at my father. My breathing is difficult. Is this what shock means, that the air turns to glue? My sister Uche says that she has just told a family friend by text, and I almost scream, “No! Don’t tell anyone, because if we tell people, then it becomes true.” My husband is saying, “Breathe slowly; drink some of this water.” My housecoat, my lockdown staple, is lying crumpled on the floor. Later, my brother Kene will jokingly say, “You better not get any shocking news in public, since you react to shock by tearing off your clothes.”

Grief is a cruel kind of education. You learn how ungentle mourning can be, how full of anger. You learn how glib condolences can feel. You learn how much grief is about language, the failure of language, and the grasping for language. Why are my sides so sore and achy? It’s from crying, I’m told. I did not know that we cry with our muscles. The pain is not surprising, but its physicality is, my tongue unbearably bitter, as though I ate a loathed meal and forgot to clean my teeth, on my chest a heavy, awful weight, and inside my body a sensation of eternal dissolving. My heart—my actual physical heart, nothing figurative here—is running away from me, has become its own separate thing, beating too fast, its rhythms at odds with mine. This is an affliction not merely of the spirit but of the body. Flesh, muscles, organs are all compromised. No physical position is comfortable. For weeks, my stomach is in turmoil, tense and tight with foreboding, the ever-present certainty that somebody else will die, that more will be lost. One morning, Okey calls me a little earlier than usual, and I think, Just tell me, tell me immediately, who has died now. Is it Mummy?

Because I loved my father so much, so fiercely, so tenderly, I always at the back of my mind feared this day. But lulled by his relatively good health, I thought we had time. I thought it was not yet time. “I was so sure Daddy was nineties material,” my brother Kene says. We all did. But did I sense a truth that I also fully denied? Did my spirit know, the way anxiety sat sharply like claws in my stomach once I heard that he was unwell, the hovering, darkening pall that I could neither name nor shake off? I am the Family Worrier, but even for me it was extreme, how desperately I wished that Nigerian airports were open so I could get on a flight to Lagos, and then on a flight to Asaba and drive the hour to my hometown to see my father for myself. So I knew. I was so close to my father that I knew, without wanting to know, without fully knowing that I knew. A thing like this, dreaded for so long, comes at last, and among the avalanche of emotions, there is a bitter and unbearable relief. It comes as a form of aggression, this relief, bringing with it strangely pugnacious thoughts. Enemies beware: the worst has happened; my father is gone; my madness will now bare itself.

There is value in that Igbo way, that African way, of grappling with grief, the performative, expressive outward mourning, where you take every call and you tell and retell the story of what happened, where isolation is anathema and “stop crying” a refrain. But I am not ready. I talk only to my closest family. It is instinctive, my recoiling. I imagine the bewilderment of some relatives, their disapproval even. At first, it is a protective stance, but later it is because I want to sit alone with my grief.

I last saw my father in person on March 5, just before the coronavirus changed the world. Okey and I went from Lagos to Abba. “Don’t tell anyone I’m coming,” I told my parents, to ward off visitors. “I just want a long weekend of bonding with you two.”

The photos from that visit make me weep. In the selfies, we took just before Okey and I left, my father is smiling and then laughing because Okey and I are being goofy. I had no idea. I planned to be back in May for a longer visit so that we could finally record some of the stories he had told me over the years about his grandmother, his father, his childhood. He would finally show me where his grandmother’s sacred tree had stood. I had not known this part of Igbo cosmology—that some people believed that a special tree, called an ogbu chi, was the repository of their chi, their personal spirit. My father’s father was kidnapped in his youth by relatives and taken to be sold to Aro slave traders, but they rejected him because of a large sore on his leg (he walked, my father said, with a slight limp), and, when he returned home, his mother looked and saw that it was him, and, crying and screaming, she ran to her tree to touch it, to thank her chi for saving her son.

My father’s past is familiar to me because of stories told and retold, and yet I always planned to document them better, to record him speaking. I kept planning to, thinking we had time. “We will do it next time, Daddy,” I’d say, and he would say, “O.K. Next time.” There is a sensation that is frightening, of a receding, of an ancestry slipping away, but at least I am left with enough for myth, if not memory.

I am writing about my father in the past tense, and I cannot believe I am writing about my father in the past tense.